An exploration of what to avoid when investing into cryptocurrency

Inversion as a mental model is the process of approaching a problem from the perspective of analysing what one must do to either cause it to occur or to make it worse.

Charlie Munger, the right-hand man of legendary investor Warren Buffet, is known for his idioms and ways of thinking to help understand how the world works. One of his most famous quotes, inspired by the German mathematician Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi, relates to understanding the actions that would lead a person toward failure. Here’s the full quote from Munger:

“Invert, always invert: Turn a situation or problem upside down. Look at it backward. What happens if all our plans go wrong? Where don’t we want to go, and how do you get there? Instead of looking for success, make a list of how to fail instead. Tell me where I’m going to die, that is, so I don’t go there”.

The concept of learning where one will completely fail, so they do not go there can be applied to the decision-making process inherent to investing.

In an investment context, the equivalent of this would be to lose all of one’s money, to realise a 100% capital loss. To understand how this can occur is to realise the actions, thought processes, and attitudes that may cause a 100% loss of capital.

This fortnight’s piece will discuss the commonly accepted means of analysing cryptocurrency investment opportunities, inverting it, and discussing a list of how to fail in order to understand how to succeed.

Step 1: Take out loans, engage in looping and over-leverage

Another relevant quote from Buffet goes, “We believe almost anything can happen in financial markets. And the only way smart people can get clobbered, really, is through leverage.”

Leverage acts as a double-edged sword that can boost returns when markets rise while forcing individuals to realise steep losses where markets fall. The use of leverage has been prominent in crypto since the founding of the cryptocurrency derivatives exchange, Bitmex, in 2014.

The primary means individuals use to gain leveraged exposure to crypto assets are perpetual futures contracts on an underlying token. While this type of derivative contract had been proposed in the past, notably by economist Robert Shiller in 1992, Bitmex was the first market to invent and introduce the financial instrument.

In just the past 24hrs as of 18th of July, $117m worth of positions in perpetual contracts have been liquidated.

Here are two examples of exchanges that offer perpetual contracts to give a sense of how accessible and widespread leverage can be within the crypto space;

On larger exchanges, investors can take up to 125x leverage on BTC USDT perpetual contracts up to $50,000 and 100x leverage on ETH USDT perpetual contracts up to $10,000.

This level of leverage means that if the price of Bitcoin declines 0.8% or more while an individual longs these contracts, they will lose all of their investment.

To access said leverage, an investor simply needs to pass a 14-question quiz on the risks involved, the answers to which can be easily accessed through a simple Google search.

Several smaller brokerage platforms allow individuals to take up to 200x leverage, wherein a 0.5% move could result in a total investment loss. No quizzes are required to be passed on some of these exchanges.

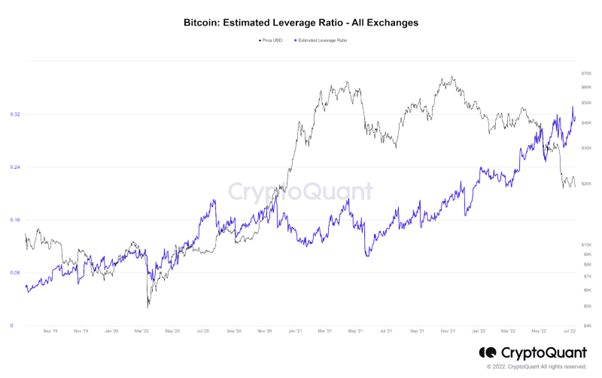

Despite the downturn that the crypto market has experienced this year, the relative ratio of leveraged positions to non-leveraged open interest remains at near all-time highs.

Other means to access even higher levels of leverage are possible through the power of decentralised finance.

Through the aptly named ‘degenbox’ strategy involving Anchor Protocol and Abracadabra.money, users could deposit UST into the strategy, wherein the protocol would engage in a series of ‘looping’, effectively borrowing against the UST locked in Anchor to acquire aUST, which is borrowed against to acquire even more aUST and so on.

Such a strategy would result in a total loss of capital should UST depeg to $0.97 or less, which it ultimately did in May 2022.

The pervasiveness of leverage in crypto was even commented on by ‘Big Short’ fund manager Micheal Burry, commenting in June 2021 that “the problem with crypto, as in most things, is the leverage.” and that “If you don’t know how much leverage is in crypto, you don’t know anything about crypto, no matter how much else you think you know”.

A quick path to failure in crypto is to engage high levels of leverage, long or short.

Step 2: Have a ‘weak stomach’ and demonstrate extreme emotional volatility

As Peter Lynch, former head of the Fidelity Magellan fund in the ‘70s & ’80s describes… ”in investing; the key organ isn’t the brain, it’s the stomach. When things start to decline – there are bad headlines in the papers and on television – will you have the stomach for the market volatility and the broad-based pessimism that tends to come with it?”

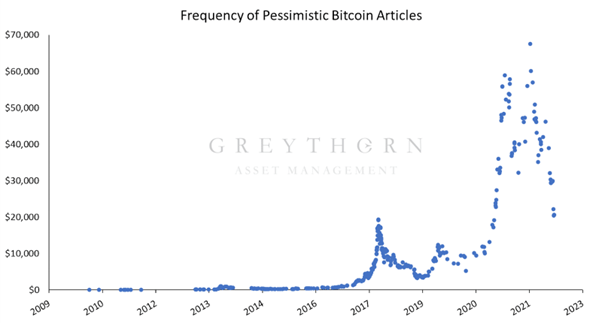

Cryptocurrency, and Bitcoin more specifically, is no stranger to bad headlines.

Website bitcoinisdead.org has a collection of 385 individual articles declaring that Bitcoin is dead, with titles ranging from ‘Crypto is Dead” in May 2022 to ‘No Investment Strategies are worse than Cryptocurrencies’ in December 2018.

Notably, the volume of articles stating the end of crypto tends to be most dense during relative cycle bottoms.

Giving in to fear and selling during these periods would result in notable underperformance for an individual over the long term.

In addition to this reporting from traditional media, Bitcoin is far more volatile than traditional assets. From January 2018 through June 2019, Bitcoin experienced average daily price movements of 2.67% to the upside or downside. This is especially volatile compared to the S&P 500 index, which has experienced 1% daily volatility over the long term.

Not being able to emotionally handle downward price volatility is the key to losing capital with crypto over the long term.

Step 3: Double down on ICO’s, IDO’s and IEO’s

Using data from CRYPTORANK.IO as of 1 July 2022, we observed that since January 2017, the crypto space has raised approximately $19 – $22 billion through initial offerings to the public (an initial coin ‘ICO’, decentralised exchange ‘IDO,’ or exchange offering ‘IEO’).

Among this group is the blockchain protocol EOS, which raised a staggering $4.2 billion in June 2018, Incodium ($1.5 billion), and Bitdao ($379 million).

While there have been offerings that have resulted in spectacular gains for early investors, such as Tron (currently delivering 32x for investors & 158x at its highs), Chainlink (currently 58x for investors and 480x at highs), and Decentraland (33.28x, and 243x respectively), the overall performance of initial offerings compared to Bitcoin has been underwhelming.

Of the 1002 crypto offerings included in the data, only 205 (20.5%) delivered a positive return to investors over the long term.

Entering into an equal-weighted position in all offerings and holding the tokens until today would have resulted in a total return of 84% over the five years, a respectable return of 12.97% p.a. in its own right, but severely lagging Bitcoin’s annual performance of approximately 82.6%.

While an investor could have achieved exceptional returns by concentrating into a few coins that became big winners, the odds of achieving this have been low. 87 (8.68%) initial offerings have returned returns greater than 3x, while 308 (30.7%) have delivered returns of -95% or worse.

Making large, concentrated bets on new crypto projects and doubling down or ‘buying the dip’ on nearly one-third of new projects over the past five years would have resulted in a severe loss of capital.

What to look out for when evaluating a losing project

While the first half of this piece has focused on the actions an individual can take to fail as a crypto investor such as taking out exorbitant leverage, being susceptible to emotional volatility or making concentrated bets on token offerings, we will now focus on inverting good methods of project evaluation to ultimately learn which projects to avoid.

1) Invest in a project that does not solve a problem or a token that has no value or utility

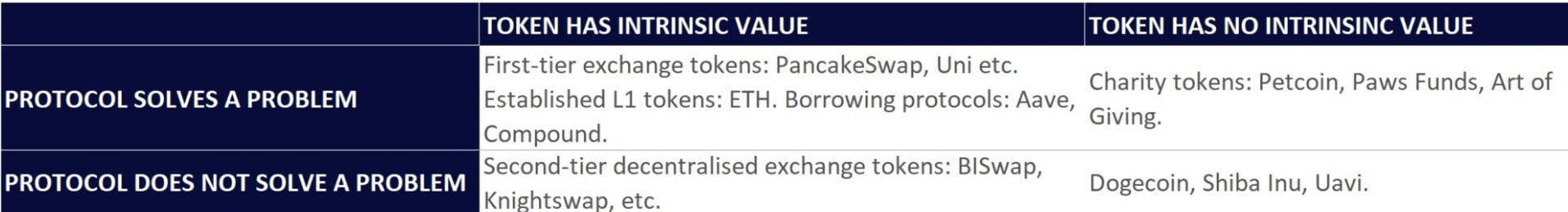

Within cryptocurrencies, there exists a spectrum of existing protocols & tokens that meet this criteria. The table below highlights the characteristics that can exist, with intrinsic value meaning the potential for a token to deliver a return to investors on its own economic merits.

Protocols can solve a problem and have intrinsic value; an example is PancakSwap which provides a lower fee to swap between cryptos. Owners of the native token of PancakeSwap, CAKE, are entitled to a percentage of fees on these trades.

Other decentralised exchanges (‘DEX’) such as BiSwap or Knightswap do have intrinsic value in that; similarly, native token holders are entitled to fees, but they do not necessarily solve a problem in that their protocols are less useful and attract less liquidity than larger DEX’s.

A token can solve a problem but have no intrinsic value. An example includes a charity token such as Petcoin. Petcoin is used to raise capital to combat animal abuse, solving a problem. Still, it has no intrinsic value as holders of Petcoin will not experience capital appreciation through any means other than speculation.

Finally, a token can have no intrinsic value and fail to solve a problem. Dogecoin fits this definition as there is no cap on the number of DOGE that can be mined, meaning there is no scarcity. In addition to this, DOGE does not serve as a reasonable currency due to its lack of utility and capacity to serve as a store of value.

The investor seeking to lose would focus on investing in tokens located in the bottom right quadrant of the above table, tokens that are essentially worthless.

2) Invest in a project with unsustainable tokenomics

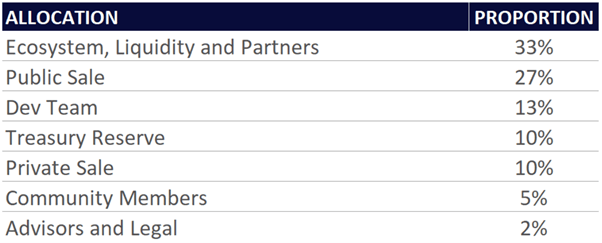

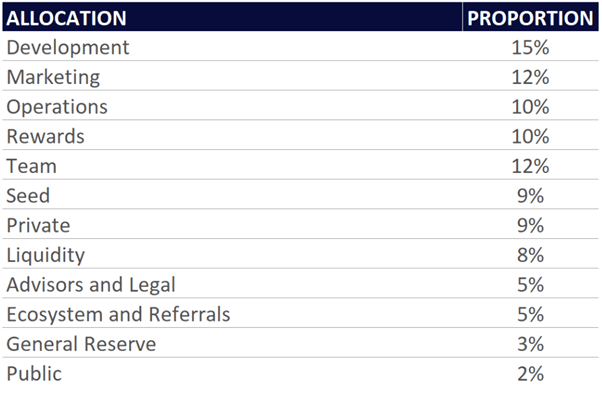

A project with good tokenomics will have an allocation of tokens wherein there is a sizeable allocation towards the project’s user base or community, a private sale proportionally smaller than the public sale, reasonable allocations to the team or advisers, room for future token sales to spur growth, and a vesting schedule attached to all insiders and institutional investors.

An example of such an allocation may follow the lines of the hypothetical distribution below:

The allocations to the public sale, partners, team, and private sale may involve a vesting schedule wherein 10% of tokens are initially unlocked, with the remaining 90% linearly vested monthly over 12-24 months.

This structure would help maintain the token’s value at launch and avoid large selling pressure directly after the offering. The allocation to the treasury reserve and ecosystem will serve to allow the protocol to grow into the future.

Conversely, investors seeking to lose in crypto should look for a protocol with tokenomics that are an inverse of the above — high allocations to insiders, advisors, and private rounds mired by confusing language that obscures the entire offering. Such an example may include the following as shown in Figure 5.

In the case of this token, the allocations to the team, advisors, seed & private investors amount to 35% of the total token supply. Furthermore, the allocations to development, marketing, and operations could also be interpreted as team allocations.

This token did have some vesting schedules for the insiders and partners, however, 67% of the allocation to the public were unlocked immediately after the offering. This unlock resulted in retail investors extracting too much liquidity from the system by immediately selling, causing the token’s value to decline significantly on its first day of trading.

As a retail investor in this token, your share of the circulating tokens will ultimately crater as the allocations to team and insiders are unlocked, with the supply of tokens increasing 50x over the coming years.

An investor who missed out on an allocation in the public round and opted to purchase the tokens once the IDO was completed would ultimately see a loss of 95% over the next 6 months.

Purchasing tokens with significant upcoming token unlocks, high allocations to the team & insiders, and low allocations to the protocol’s reserve or treasury is a surefire means to capital destruction.

3) Overpay for a project relative to its future potential and addressable market.

As Warren Buffet states, ‘Price is what you pay, value is what you get.’

To realise losses investing in cryptocurrency, focus on purchasing overvalued protocols where everything and more has to go right to realise a satisfactory return.

At its peak value in April 2021, CAKE was trading for $42.69 or a fully diluted valuation of $32 billion.

For this valuation to be reasonable, given the 1.68% risk-free rate of the time (10-year U.S treasury bill) and applying a lenient crypto risk premium of 8%, the PancakeSwap protocol needed to be able to deliver an equivalent 9.68% potential dividend to its token holders.

This potential dividend equates to a distribution of $3.1 billion from the protocol in perpetuity.

As discussed in our last fortnightly article, PancakeSwap can effectively deliver 0.08% of each swap as a dividend to token holders.

Therefore, to generate $3.1 billion in cash flow there needs to be yearly trading volume of $3.875 trillion on the PancakeSwap platform ($3.1 billion/ 0.0008 = $3.875 trillion).

In May 2021, PancakeSwap experienced its greatest ever month for volume traded at $51.81 billion. If we were to assume that the exchange could replicate this volume over 12 months, there would be an annual volume of $622 billion, only 16% of the volume necessary to justify its valuation.

While there was always the potential for PancakeSwap to increase its trading fees to distribute a more significant percentage of volume to token holders, the valuation of CAKE relative to its actual performance was considerably elevated.

All centralised crypto exchanges saw a total trading volume of approximately $14 trillion in 2021, with Binance facilitating 67% of trades in the year with $9.5 trillion. Therefore, CAKE needed to attract 40.8% of Binance’s volume in 2021 to justify a $32 billion valuation.

While proponents of CAKE can argue that CAKE is a growth asset that doesn’t need to generate considerable distributions in 2021 if it can continue to grow exponentially into the future, an individual investing in CAKE was pricing in perfection and then some.

A secondary example of overpaying for a crypto protocol’s growth potentially includes metaverse-focused projects Sandbox (‘SAND’), and Decentraland (‘MANA’).

As of April 6, 2022, Sandbox had 1,180 daily active users, while Decentraland had 978.

Given SAND’s fully diluted market cap of $9.4 billion at the time, and MANA’s valuation of $5.5 billion, each user was valued at $7.97 million for SAND and $5.6 million for MANA.

These values contrast against Electronic Arts’ (a traditional video game developer) $34 billion market cap, where if we were to determine the value of each user for a single game, FIFA Ultimate Team with 6 million daily active users, each user is valued at $5,750.

While the metaverse projects of SAND and MANA likely have more significant growth potential compared to a stalwart such as Electronic Arts, such a large discrepancy in the value of a user is irrational. How likely is it that these projects are able to gather far more daily active users than established gaming brands to justify their valuations?

Investors seeking negative returns should entirely disregard valuation and a protocol’s future potential growth.

CONCLUSION

By focusing on what one should do to fail when investing in cryptocurrency markets, individuals can learn of the pitfalls they are likely to face in order to succeed moving forward.

The individual investor who seeks to fail should do the following:

1) Utilise significant leverage.

2) Demonstrate poor emotional volatility.

3) Double down on, and invest in, initial token offerings with no clear roadmap.

4) Invest in a token that does not solve a problem, has no intrinsic value, or both.

5) Invest in projects with poor or unsustainable tokenomics.

6) Overpay for the growth of a project relative to its future potential or addressable market.

These six points represent only a tiny fraction of a crypto investor’s potential mistakes. Individuals must act cautiously when evaluating potential investments.

We hope that by reading this piece, you have learned of some places that crypto investors fail at, so that you do not go there.

REFERENCES

- Coingecko <Coingecko.com>.

- Coinglass, Total Liquidation Data, <https://www.coinglass.com/LiquidationData>.

- Daniel Hoechel, Larissa Karthaus and Markus Schmid, (2021), ‘The Long-Run Performance of IPOs Revisited’, <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2929733>.

- Etoro, ‘Why does Bitcoin’s price fluctuate so much?’, <https://www.etoro.com/crypto/why-bitcoin-fluctuates/>.

- Evgeny Lyandres, Berardino Palazzo and Daniel Rabetti, (2020), ‘ICO Success and Post ICO Performance’, <https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.2022.4312>.

- Farnam Street, ‘Inversion and the Power of Avoiding Stupidity’, <https://fs.blog/inversion/>.

- Financial Samurai, ‘Average Daily Percent Move of The Stock Market: S&P Volatility Returns’, <https://www.financialsamurai.com/average-daily-percent-move-of-the-stock-market/> .

- Investment Masters Class, ‘Leverage’, <http://mastersinvest.com/leveragequotes>.

- James Clear, ‘Inversion: The Crucial Thinking Skill Nobody Ever Taught You’, <https://jamesclear.com/inversion>.

- Jay R. Ritter, (1991), ‘The Long-Run Performance of Initial Public Offerings’ ,The Journal of Finance, <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1991.tb03743.x#jofi3743-bib-0030>.

- Jerry Feng, <Bitcoinisdead.org>.

- John Kehoe, Australian Financial Review, ‘Revealed: Charlie Munger’s best investment tips’ <https://www.afr.com/markets/equity-markets/revealed-charlie-munger-s-best-investment-tips-20220705-p5az7y>.

- Molly Sloan, Drift, ‘Invert, Always Invert: A Secret To Solving The Most Difficult Problems.’, <https://www.drift.com/blog/invert/> .

- Raphael Minter, ‘PancakeSwap (CAKE) Plummeted to New Volume Lows in February as Market Slumps’, BeinCrypto, <https://beincrypto.com/pancakeswap-cake-plummeted-to-new-volume-lows-in-february-as-market-slumps/>.

- Sam Reynolds, ‘Metaverse Majors Struggle as User Base Falls Short of Market Expectations’, Condesk, <https://www.coindesk.com/markets/2022/04/06/metaverse-majors-struggle-as-user-base-falls-short-of-market-expectations/>.

- Shiller, Robert J, 1993. “Measuring Asset Values for Cash Settlement in Derivative Markets: Hedonic Repeated Measures Indices and Perpetual Futures,” Journal of Finance, American Finance Association, vol. 48(3), pages 911-931, July.

Important notice and disclaimer

This presentation has been prepared by Greythorn Asset Management Pty Ltd (ABN 96 621 995 659) (Greythorn). The information in this presentation should be regarded as general information only rather than investment advice and financial advice. It is not an advertisement nor is it a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any financial instruments or to participate in any particular trading strategy. In preparing this document Greythorn did not take into account the investment objectives, financial circumstance or particular needs of any recipient who receives or reads it. Before making any investment decisions, recipients of this presentation should consider their own personal circumstances and seek professional advice from their accountant, lawyer or other professional adviser.

This presentation contains statements, opinions, projections, forecasts and other material (forward looking statements), based on various assumptions. Greythorn is not obliged to update the information. Those assumptions may or may not prove to be correct. None of Greythorn, its officers, employees, agents, advisers or any other person named in this presentation makes any representation as to the accuracy or likelihood of fulfilment of any forward looking statements or any of the assumptions upon which they are based.

Greythorn and its officers, employees, agents and advisers give no warranty, representation or guarantee as to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information contained in this presentation. None of Greythorn and its officers, employees, agents and advisers accept, to the extent permitted by law, responsibility for any loss, claim, damages, costs or expenses arising out of, or in connection with, the information contained in this presentation.

This presentation is the property of Greythorn. By receiving this presentation, the recipient agrees to keep its content confidential and agrees not to copy, supply, disseminate or disclose any information in relation to its content without written consent.

Copyright 2022 by Greythorn Asset Management Pty Ltd.