A common term used within traditional financial markets is the concept of Enterprise Value (EV).

Enterprise value is a measure of a company’s total value that incorporates the market capitalisation of a company, its cash, cash equivalents, and debt. The formula for enterprise value is as follows.

EV = Market Value of Equity + Preferred Equity + Market Value of Debt + Minority Interest- Cash & Cash Equivalents.

This metric is important in that it represents the ‘true’ value of an asset as it incorporates what the company holds in cash and what it owes to external parties.

A company may appear cheap when one only evaluates the market value of its equity (market capitalisation), but when its debt and cash holdings are considered, it can be expensive.

An example of this is the American telecommunications company AT&T. Based on its valuation as of 17/06/2022, its market capitalisation is $139.17B. It has an operating income over the past 12 months of $32.94B. This gives the company a price to operating income ratio of 4.2, making it appear to be a significantly undervalued potential investment based on its inherent cash flow.

However, when you add its total debt of $237.59B and deduct its cash holdings of $38.57B from the market capitalisation, an enterprise value of $338.19B is reached.

From this, we discover that the company is actually trading at an enterprise value to operating income ratio of 10.2 and is far less undervalued than initially conceived.

When divided by a metric such as operating income or net income, the enterprise value has historically been a popular metric used to determine whether a company is a target for a potential takeover.

A company with a low enterprise value to operating income ratio is generally financially strong. It has significant cash holdings on its balance sheet relative to its debt and strong cash flows to support internal investment or shareholder returns.

Research from Tobias Carlisle and Wesley Gray in the book ‘Quantitative Value’ has shown that companies with enterprise values to operating income in the bottom quintile of the investment universe have significantly outperformed the broader market, delivering annual returns of 17.9% from 1973 to 2017 compared to 10.2% from the S&P 500.

Within this bottom quintile, a subsection of companies has delivered even greater annualised returns of 50.4%, albeit with far greater volatility.

This subsection is those companies with negative enterprise values, where the cash and cash equivalents held by the company are greater than its combined market cap, debt, and other obligations.

These companies are often scary to invest in, with tremendous headwinds facing their industry, potentially looming lawsuits, or speculation of potential accounting fraud that serves to drive down the value of its equity significantly below the cash held on its balance sheet.

Despite these conditions, research has demonstrated that the perceived risks tend to be far greater than the actual risks. The companies ultimately experience significant share price appreciation following a change in their perception by the market.

Why is this metric important to a crypto-focused asset manager such as Greythorn?

This is because as the cryptocurrency market potentially enters into a crypto winter similar to that of December 2013 to January 2015 or December 2017 to December 2018, there will be cryptocurrency projects or protocols that emerge where the value held in the treasury of these projects is greater than the total market capitalisation of all existing tokens.

In essence, there will likely be cryptocurrencies that have negative enterprise values and present significant opportunities to individuals who can extract value from the project treasuries.

Furthermore, the protocols with sizeable treasury reserves will be better capitalised to withstand a coming bear market. The project’s development team can use the reserves to advance its mission and use case further.

According to data from CryptoRank.IO, the 1000 largest ICOs, IEOs, and IDOs have raised approximately $2.88b since January 2020.

The vast majority of these funds have been raised from stablecoins and layer one native tokens, primarily Ethereum, to serve as the capital to fuel these projects as they build out their use cases.

As of June 10, Bitcoin.com estimated that Decentralised Autonomous Organisations (DAO) held assets equivalent to approximately $10 billion with 1.7 million individual governance token holders.

With the crypto market cap excluding Bitcoin down 69% from all-time highs and approximately 79% of cryptocurrencies issued since January 2020 currently trading below their issue price, many protocols may have a current market capitalisation that is less than the value of their treasury. This presents a potential investment opportunity.

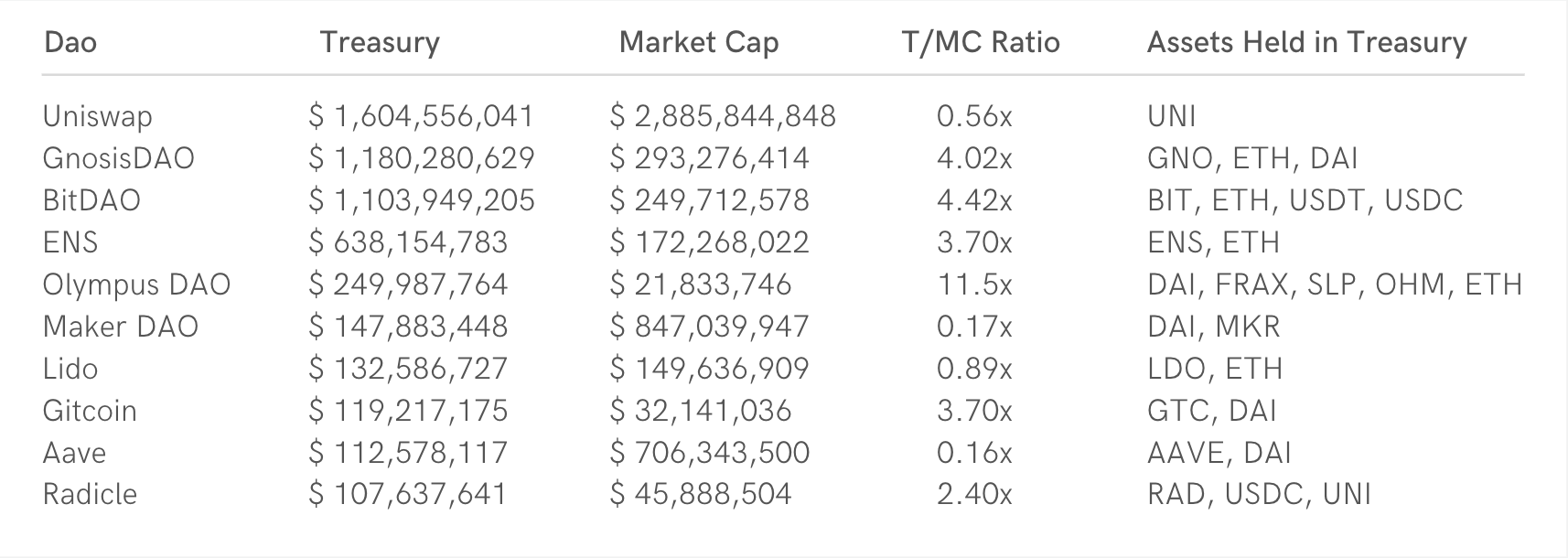

The following table shows the amount held in the treasuries of the largest DAOs compared to their market capitalisation.

The T/MC ratio represents the value that a governance token holder would hypothetically be entitled to by investing in the token. In this manner, it acts as somewhat of a net current asset to market cap ratio, the amount that could hypothetically be airdropped to governance token holders. All else being equal, a token with a higher T/MC ratio can be considered a better investment opportunity than a token with a lower T/MC ratio.

While many of the above DAOs are trading at a significant discount to their treasury value, many factors undermine the potential value opportunity. Namely, for many projects, such as Gnosis, BitDao, ENS, Gitcoin, and Radicle, a significant proportion of the treasury value is held in the illiquid native governance token of the protocol. In the case of Gitcoin, approximately 94% of the treasury is held in GTC tokens which would have essentially zero value in the case of liquidation.

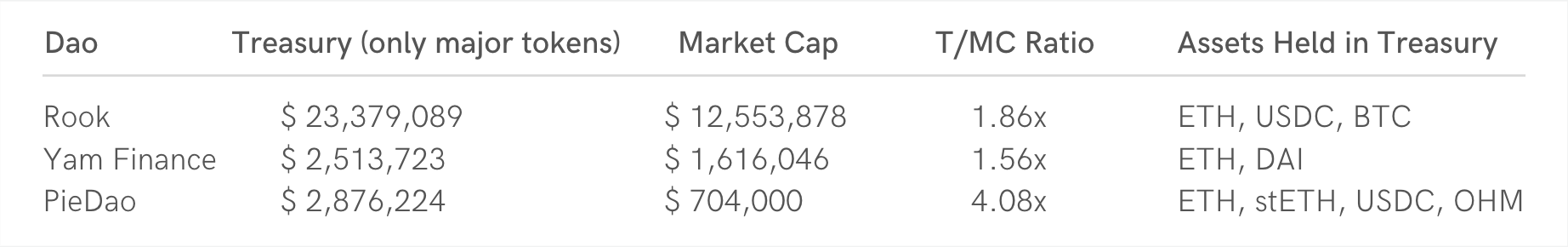

However, potential opportunities can be found within the DAO space, particularly in very small market capitalisation protocols.

The governance tokens of the above DAOs are currently trading at a significant discount to the value of their treasury, even when only including the value of major cryptocurrencies.

Issues with taking a negative enterprise value approach to cryptocurrencies.

While there may be an opportunity in negative enterprise value cryptocurrencies, a variety of problems emerge with this investment approach.

Firstly, and especially with microcap cryptocurrencies, the tokens can be highly illiquid, with the top holders completely controlling the governance voting in a protocol.

In the case of PieDao, the top 20 holders of its governance token, DOUGH, control 97.31% of the voting rights in the protocol, with just one wallet currently holding 43.27% of the supply.

With a significantly larger market cap, even Rook has the top 20 holders controlling 90.08% of its tokens.

It would be challenging, if not impossible, for any individual to accumulate enough of the governance tokens of these protocols to push through a proposal to distribute the treasury to token holders.

Secondly, it is unknown whether governance token holders are entitled to any proportion of the treasury whatsoever.

While a share in common stock gives investors an entitlement to dividends and the equity of a company, backed by property law, it is uncertain what rights governance tokens confer to their holders.

While Governance tokens nominally represent ownership in a decentralised protocol and ordinarily offer the right to vote on governance-related matters, the tokens are often not backed by hard code or legal precedent. Investors are instead relying on the good nature of large token holders or developers to comply with the outcome of a governance vote.

Common stock in a public corporation entitles a holder to the dividends of the company, but the vast majority of governance tokens confer no such rights, only the ‘promise that a vote will eventually pass to reward the token holders with dividends’. This was essentially echoed by Yearn Finance creator Anton Cronje who in July 2020 stated that the YFI token was “worthless” as it did not distribute cash flows to the protocol owners.

Thirdly, many DAOs were created to fulfil some mission or goal. Many of the initial creators and token holders are dedicated to achieving this mission rather than purely aiming to improve the wealth of token holders. It could be challenging to convince the community of a protocol of the economic benefit they could derive from liquidating the project, especially when they believe in its mission or have been holding the token through an 80%+ decrease in value.

The individuals actively working on developing a project may also not wish to see it liquidated and could essentially ignore the result of a governance poll to distribute the treasury. This case could be somewhat similar to an investor base fighting with a company’s management over the lack of a decision to liquidate the company out of management’s self-interest in retaining their jobs.

The cryptocurrency space has yet to see a cryptocurrency protocol decide to liquidate itself to realise value for investors.

While there are problems present in attempting to execute a strategy similar to that of buying negative enterprise value stocks within the cryptocurrency space, significant value opportunities will emerge as the market begins to enter a crypto-winter.

Similar to negative EV stocks dramatically outperforming the greater equities market, cryptocurrency projects with significant treasury reserves relative to their market caps could outperform the greater crypto market over the coming years.

Conclusion

This piece has discussed the performance of low and negative enterprise value equities, showing how they have outperformed the market over the past 50 years, albeit with additional risks specific to each company.

This phenomenon may be seen in cryptocurrency projects over the coming years. Those protocols with low market capitalisations relative to trading fees earned by the protocol or the value of their treasuries may represent a significant value opportunity to investors who can unlock said value.

Even if an investor cannot extract the treasury value from a project, a cryptocurrency protocol with significant treasury reserves relative to its market capitalisation will inherently present a more favourable risk-return relationship than projects that have undercapitalised treasuries. The project developers can use the project treasury to continue to evolve the project and increase the chance that a breakthrough will occur that will deliver value to token holders.

References

Alan Bochman, ‘Returns on Negative Enterprise Value Stocks: Money For Nothing?’, Enterprising Investor, 2013, <https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2013/07/10/returns-on-negative-enterprise-value-stocks-money-for-nothing/>.

Nikita Elkin, ‘Beat The Market With The Acquirers Multiple: Review, Performance and Backtest’, 2020, < https://finbox.com/blog/what-is-the-acquirers-multiple-review-performance-backtest/ >.

Tikr Terminal, ‘AT&T Financials’.

Tobias Carlisle, Wesley Gray, ‘Quantitative Value: A Practitioner’s Guide to Automating Intelligent Investment and Eliminating Behavioural Errors’, 2012.

Squeeze Metrics, ‘The implied order book’, 2020.

Important notice and disclaimer

This presentation has been prepared by Greythorn Asset Management Pty Ltd (ABN 96 621 995 659) (Greythorn). The information in this presentation should be regarded as general information only rather than investment advice and financial advice. It is not an advertisement nor is it a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any financial instruments or to participate in any particular trading strategy. In preparing this document Greythorn did not take into account the investment objectives, financial circumstance or particular needs of any recipient who receives or reads it. Before making any investment decisions, recipients of this presentation should consider their own personal circumstances and seek professional advice from their accountant, lawyer or other professional adviser.

This presentation contains statements, opinions, projections, forecasts and other material (forward looking statements), based on various assumptions. Greythorn is not obliged to update the information. Those assumptions may or may not prove to be correct. None of Greythorn, its officers, employees, agents, advisers or any other person named in this presentation makes any representation as to the accuracy or likelihood of fulfilment of any forward looking statements or any of the assumptions upon which they are based.

Greythorn and its officers, employees, agents and advisers give no warranty, representation or guarantee as to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information contained in this presentation. None of Greythorn and its officers, employees, agents and advisers accept, to the extent permitted by law, responsibility for any loss, claim, damages, costs or expenses arising out of, or in connection with, the information contained in this presentation.

This presentation is the property of Greythorn. By receiving this presentation, the recipient agrees to keep its content confidential and agrees not to copy, supply, disseminate or disclose any information in relation to its content without written consent.